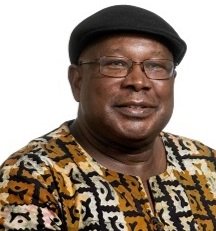

Ep4: We Are Nature with James Ogude

“Ubuntu collapses the dichotomy that we create between humans and non humans - between culture and nature.”

We welcome Professor James Ogude to explore the concept of Ubuntu - a Nguni Bantu term meaning "humanity" that translates as "I am because we are" or "I am because you are". Together, we discuss how the humanities can complement scientific perspectives, and how modern cultures can learn from lost languages and Indigenous knowledge, particularly in relation to community and a rebalanced relationship with the Earth.

Professor James Ogude is the Director at the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship, University of Pretoria and Director of the African Observatory for Environmental Humanities. He is currently leading a Mellon funded supra-national project involving the Universities of Ghana, Makerere, Cape Town and Pretoria and is the Principal Investigator of a University of Pretoria research project on the African philosophy of Ubuntu funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation.

Show notes

Sarah and Michael’s book, Flourish: Design Paradigms for Our Planetary Emergency is now available at Triarchy Press.

Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk and peace activist Thích Nhất Hạnh talks about interbeing, an underlying state of connectedness between all things that interdependently co-exist.

Scientist and educator Lynn Margulis coined the term “symbiogenesis”, which refers to formation of new organisms as a result of convergence in contrast to the prevailing theory of ‘survival of the fittest’, which suggested that new organisms came about due to mutation and/or competition. Chapter 4 of Flourish goes into this paradigm with greater detail.

The African Observatory for Environmental Humanities is part of a global network of Humanities for the Environment (HfE) observatories established in 2013 to identify and explore the contributions that humanistic and artistic disciplines can make to solve global social and environmental challenges. There are 8 observatories worldwide to date – Africa, East Asia, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Australia-Pacific, Latin America, North America and Circumpolar.

In his book, Genocide in Nigeria: the Ogoni Uganda Tragedy, Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa shares his concerns about for the ethnic minority Ogoni people and their mistreatment by multinational oil companies collaborating with the Nigerian government in the Niger Delta region. His book, Silence would be Treason: Last Writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa, demonstrated his last fight for justice for the Ogoni people, indigenous rights, environmental survival and democracy before his execution by a military regime.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o was born in Kenya in 1938, and is a Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine.

Kikuyu is a Southern African language spoken in Kenya in the area between Kyeri and Nairobi.

Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht argues in his paper, “Exiting the Anthropocene and Entering the Symbiocene”, that the next era of human history, or the Symbiocene, from the Greek sumbiosis, or companionship, that implies living together for mutual benefit.

The Post-Human by Rosi Braidotti analyzes the escalating effects of post-anthropocentric thought that encompasses other species and the sustainability of the planet.

French writer Michel Serres made recourse to the idea and practice of narrative as a way of constituting a common pool of knowledge for the whole of humanity. He theorizes the “educated third element” which refers to a figure of knowledge that Serres indicated approximates that of the Harlequin: a composite figure that always has another costume underneath the one removed. It is a hybrid figure; a mixture of diverse elements and a challenge to homogeneity.

Buen vivir, "good living" or "well living” in English, is interpreted by social ecology researcher Ecuadorian Eduardo Gudynas, as a way of doing things that is community-centric, ecologically-balanced and culturally-sensitive, rooted in the cosmovisión (or worldview) of the Quechua peoples of the Andes.

Jeremy Lent is the award-winning author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning and Requiem of the Human Soul. Jeremy is also an invited speaker of Flourish Systems Change.

The South American writer Jorge Luis Borges famous quote is a translation from his 1981 interview in Spanish with El Pais.

In German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin’s essay, The Storyteller, he uses the work of 19th-century Russian writer Nikolai Leskov as a departure point to discuss the role of storytelling in society, the dangers of its decline, and how it shapes our relationship to truth, both public and private.

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, arts critic and researcher who is a member of the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. His book, Sands Talk, speaks about how indigenous thinking can save the world.

Author and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Her book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and Teachings of the Plants (2013), received best-seller awards amongst the New York Times Bestseller, the Washington Post Bestseller, and the Los Angeles Times Bestseller lists. She is also quoted in Chapter 2 of Flourish.

Architect Julia Watson’s book, Lo–TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism advocates for a design movement building on indigenous philosophy and vernacular infrastructure to generate sustainable, resilient, nature-based technology.

Cajetan Iheka’s Naturalizing Africa analyzes how African literary texts have engaged with pressing ecological problems in Africa.

Post Colonial Ecologies edited by Elizabeth DeLoughrey and George Handley is a collection on postcolonial literature and the environment that includes essays from overlooked Caribbean, Latin American, African and South Asian scholars and activists who have contributed to global environmentalism and a sense of place in literary production

Johannes Fabian is an emeritus professor of Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. He became most famous for his book, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object, that changed the way anthropologists think about their relationship with the people they study and is an important work of postcolonial critique within anthropology.

Ubuntu theology is anchored in the concept of Ubuntu beyond community and into God through the biblical category of the imago Dei, or the symbolical relation between God and humanity, that was developed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the chairperson of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa between 1996 and 1998.

Cultural critic and intellectual Edward Said’s essay, “Traveling Theory” (1982) suggests that the first time the understanding of a cultural event or phenomenon is filtered through a theoretical formulation, this formulation's strength derives directly from the source of a concrete, historical context.

Professor James Ogude is a prolific writer on Ubuntu philosophy and has written and edited a series of books on Ubuntu including Ubuntu and the Everyday, Ubuntu and Personhood, and Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community.

Transcript

Episode 4 : We Are Nature : 50 minutes

Sarah Ichioka 00:02

Hello and welcome to the Flourish Podcast where we discuss design for systems change. I'm Sarah Ichioka. I'm an urbanist, strategist, and director of Desire Lines based in Singapore. I'm delighted to co-present Flourish with Michael Pawlyn, who is the founder of Exploration Architecture, and a leading architect in regenerative design based in London.

In today's episode, we're going to be talking about a paradigm that Michael and I call symbiogenesis. It's a mouthful, but it's a term that we've borrowed from the visionary scientist and science educator Lynn Margulis, who's a key reference for our book. In Flourish, we've assembled the evidence that challenges existing stories about inherently competitive aspects of human nature. And instead, we describe a new paradigm based on making together and co-agency with the built environment.

Michael Pawlyn 01:24

And I think it's important to remember that the way we shape our cities is a reflection of the way we see ourselves. And, also to realise that the idea of us being isolated individuals, is a largely Western industrial age perspective. And you can see examples of that, for instance, in urban sprawl. So that is, it's partly a result of planning, policy and economics. But it's also partly a result of seeing ourselves as isolated individuals in a zero sum game of kind of survival of the fittest. So for instance, in other cultures, there are some really interesting ideas, such as the idea of interbeing. So that comes from the Vietnamese monk, Thích Nhất Hạnh. And the idea there is that actually, we're all in a state of interdependence, a state of connected inter-relationships.

Sarah Ichioka 02:22

Even looking at the sciences, there's plenty of recent research that suggests that both for our neighbouring species, they're much more cooperative than Darwinian survival of the fittest frame would consider and we too, as humans, have an immense capacity for altruism and cooperation. If we take that view of human nature, it would lead to a very different form of urban planning and design right, rather than the cycle you've mentioned, Michael, of a downward cycle of isolation and loneliness and dependence on our cars, we could be creating cities that produce positive feedback that leads in turn to better quality of life.

Michael Pawlyn 03:07

And that's what you mean when you use the term symbiogenesis. So as Lynn Margulis talked about it –symbiogenesis– is the idea that when organisms live in a state of symbiosis, as they evolve, they start to develop new structures that enhance that interdependence and in turn enhance the mutualistic benefits. And so we think it's a really interesting topic to be exploring in cities. How can we do the equivalent of symbiogenesis in cities?

Sarah Ichioka 03:37

Exactly and to take us out to a bigger picture, we're really honoured to have Professor James Ogude with us today and helping to draw connections between traditional forms of knowledge, particularly in a southern African context, but also connecting with traditional forms of knowledge around the world and what that these forms of knowledge and philosophy can bring to our future debate about how to be able to live in a more integrated way with the rest of nature.

Michael Pawlyn 04:23

He is the director of the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship at the University of Pretoria. He's an “A2” rated researcher by the National Research Foundation. He has just concluded a five-year project on the southern African philosophical concept of Ubuntu funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation. He's currently leading a Mellon funded supranational project involving the Universities of Ghana, Makerere, Cape Town and Pretoria. He's also the director of the African Observatory for Environmental Humanities, located at the University of Pretoria. And we're delighted that he's joining us today. Thank you, Professor Ogude, or James, if I may.

James Ogude 05:00

Thank you.

Sarah Ichioka 05:01

Very warm welcome to Flourish. We're so pleased to have you on. I wondered, as a starter, if you could share more with us about the work that you do at the African Observatory for Environmental Humanities. What does the organisation do and what does your particular research relate to at the moment?

James Ogude 05:24

Thank you. So the African Observatory for Environmental Humanities is really part of a global network of observatories that are scattered around the world. It was a project whose aim was to identify and explore and demonstrate the contributions that humanistic and artistic disciplines can make to our understanding and engagement with global environmental challenges. To foster, if you like, innovative, pragmatic ideas, and also collaborative research across national, regional and disciplinary boundaries. Our starting point is that if you look at what is now described as the age of the Anthropocene, that is, the age in which human activity is significantly reshaping, you know, the geological future of the planet and the Earth, in general, then you suddenly realise that, in fact, the humanities have a critical role to play. And what underscores this is the understanding that to shift our behaviour, our attitudes, towards the climate, towards the world, towards global warming, we have to realise that it is also about behaviour, shifting human norms, shifting human ways of looking at things, but also evoking those values that have always shaped humanity's understanding of their surroundings. And to do that, we believe you need the humanities.

So our observatory, the African Observatory takes, as its starting point, the concept of Earth keeping, which is drawn from a range of indigenous forms of ecological conservation, and is informed by spiritual ideas premised on people as Earth protectors, people as Earth keepers, rather than Earth exploiters, as it were. So in other words, we are trying to argue that, in a fundamental sense, a range of African indigenous forms of understanding of the environment has always been underpinned by the boundary between the human and the nonhuman, and, in fact, to protect, to protect the Earth. So in a nutshell, you know, our aim is at mobilising humanities, for intervention and research on climate change, but also creating dialogue with scientists.

Sarah Ichioka 08:40

Brilliant, thank you. I'm so excited to have you on. This work is so important to these interdisciplinary collaborations and the work of rediscovery as well. I mean, one of my goals, and my main hypotheses in our new book Flourish, is that we all need to tell a different story, or really a collection of different stories, in order to effectively address all of our compound crises of our industrial societies. I wonder if you'd be able to share, you know, from your and your colleagues research: Have there been stories that you think are particularly powerful or represent the kind of narrative that we should be aiming to tell instead?

James Ogude 09:25

You know we've been working on ways in which the problem of extraction in Africa has affected or has led to climate degradation, and yet our argument is that these stories, these forms of damage, need writers and storytellers. And they have always been at the forefront of the struggle against this kind of degradation of the Earth. You know, I'll give you a good example, if you look at the damage that has been done around the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, for example. It's been a symbol of a degraded environment, you know, due to reckless and irresponsible extraction practices. And the story was first brought to the attention of the world by a Nigerian writer, and activist, Ken Saro-wiwa that I'm sure you, you all know, his book, Genocide in Nigeria: The Ogoni Tragedy, has been very critical in shaping our understanding of some of these issues. The story or Silence Would be Treason, again, speaks to us in very profound ways, forcing us to grapple with some of these issues. African writers have been a witness to the destruction of African ecology. And I'm doing a paper on a leading Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o that in many ways in his works, anticipated some of the problems that we are talking about now. And my point, ultimately, is that we can rely on science to give us statistics, sometimes very grim statistics, but you have to turn data into a story that can appeal to the hearts and minds.

Michael Pawlyn 11:32

Before we go too much further, I wonder if you could just explain the concept of Ubuntu to listeners who may be unfamiliar with it, and particularly the way that Ubuntu could be a guiding philosophy for how we might approach the crises of global heating, biodiversity loss and social inequality.

James Ogude 11:51

Thank you. Look, Ubuntu for those of you who may not know, is a South, Southern African Kikuyu word. It basically means I am because you are; we are because you are. And it is premised on the idea that the full development of personhood, of our humanness comes with shared identity. And also the idea that an individual's humanity is fostered in a network of over relationships. So fundamental to the idea of Ubuntu is about relationality. Our sociality as human beings. The argument, which goes against the grain of Western thought, is that agency does not only reside in individualistic self determining and autonomous bodies, but more importantly, in relationally, constituted social persons. But Ubuntu goes further and this is, you know… Ubuntu philosophy also rests on the principle of co-agency. In other words, it places emphasis on the dialogical relationship between humans and nonhumans. Not just nature, but the totality of our universe, which among others in many African societies will also include relationships with your ancestors, supreme beings. But fundamentally, what Ubuntu does is to collapse the dichotomy that we always create between humans or non humans, the dichotomy that we create between culture and nature. So in a way, there's a sense in which I try to argue in my own work with other colleagues that some of these so called banished knowledges have a place in helping us to redress issues of of climate change and global warming, and precisely because they question the centering of the human the centering of the Anthropocene in a ways that neglects all else within our societies.

Sarah Ichioka 14:28

Are you familiar with the work of the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht? I don't know if you've come into contact with him at all, I'm sure you would have so much to talk about. He talks about being anti the term, the Anthropocene, because he sees Anthropocene as this period that we should be trying to move through as quickly as possible into a new era where we are taking much more responsibility through this sort of rediscovery of relational responsibilities to something that he calls the Symbiocene, a new aspirational era, which I hear a lot of resonances between the work you've done through this, this five year long project, looking at Ubuntu and the current work that you're undertaking, as part of the global network.

James Ogude 15:23

I have not read his work but I definitely would from what you're telling me. His ideas resonate deeply with what I'm trying to push for, in the context of environmental discourse,

Sarah Ichioka 15:37

And he should absolutely know about your work too.

James Ogude 15:41

I am familiar, I don't know whether you are familiar with Rosi Braidotti has got a fascinating text called The Post-human, which also talks about this. And a fascinating French writer, who is called Michel Serres himself, you know, talks about a return to these banished knowledges. In fact, he calls them the Third Law: instead of just saying, love thy neighbour as you love yourself, you should be saying, love the Earth, as you love yourself, as the third law.

Michael Pawlyn 16:19

I was really interested in what you were saying there about co-agency and how agency does not just reside in individuality. I think that's such an important point. Because it's becoming more and more obvious that we're only really going to rise to the challenge of the planetary emergency, through expanding our agency into forms of co-agency to use your term. And I'm really interested to know more about what is common and also what is distinct about Ubuntu compared to say, concepts of interbeing, which is Thích Nhất Hạnh’s term – he's the Vietnamese monk and philosopher. Does Ubuntu describe certain things that you think are sort of common to humanity, as well as things that are quite specific to Africa?

James Ogude 17:01

My idea is that some of these concepts, you know, like Ubuntu, they travel, and as they travel, they also change and mutate very much in the same way that human societies have always done. But fundamentally, through the research that we've done, I've found a number of value systems, you know, because we are human beings, at the end of the day, we are the same. When you think about it, I've found that in a number of societies, there are similar value systems that are strikingly very much the same as the value of the principle of Ubuntu. We found when I was working with one lady from Germany, who is based in Hungary, and she came up with a fascinating idea called Buen Vivir, you know, I don't know whether I'm pronouncing it properly. In South America, that basically resonates with the kind of value systems that Ubuntu encourages. I'm in conversation with a lady too from India, she was particularly struck by the similarity between Ubuntu and certain Indian value systems that she's trying to use to mobilise her community on environmental issues. And you could go on in China and, and many other places, you know, they are strikingly similar even in Western thought. There is a general understanding about a basic minimum, what they call human rights, that we all have to agree on. And that cuts across you know: when you cross that line, then it is not just about you, it’s about a transgression against, you know, the whole community.

Sarah Ichioka 19:07

Referring back to Professor Ogude’s point about the need for conversation between the humanities and the natural sciences thinkers like Jeremy Lent, are pointing out that many of these traditional philosophies have increasing resonance with cutting edge scientific discoveries as well, that we actually all exist in a state of interbeing, both in the way that societies work, and also the way that our whole concept of individuality is actually false that we, ourselves contain multitudes, right, which literally, have multiple constituent parts.

Michael Pawlyn 19:47

Yeah, there was a wonderful quote from the South American writer, Jorge Luis Borges, who, who kind of counters this idea that identity resides in the isolated individual. He says, “I'm not sure that I exist, actually, I am all the writers I have read, all the people I have met, all the women that I have loved, all the cities I've visited.”

James Ogude 20:10

Brilliant, really well put, you know, I'm a literary scholar, you know, much of my thinking has been shaped by a whole range of stuff that I've read, from your German literature, your French literature, your Russian literature, Latin American literature, American literature, especially, you know, African American literature, has been so central to some of our sensibilities. So, all these, in many ways, shape what we think, I don't know whether you know, the German philosopher, Walter Benjamin. Walter Benjamin has a fascinating thing, you know, it is what he calls the storyteller. And the storyteller simply tells us that the making of identities has always been about the stay-at-home, and also the traveller. So the traveller goes out there, comes back with new ideas, and these new ideas enter into dialogue, and or if you like, conjugation with the local law, the local value system, that's how societies the world all over, have always been shaped.

Michael Pawlyn 21:28

I wonder if we could move on now to thinking partly about, you know, how we live and how that might need to change and also how that is connected with the way we shape our cities. Because, you know, urban sprawl, particularly as seen in western industrialised countries, you know, could in some ways be seen as embodying the opposite of Ubuntu - isolated buildings, leading to increasingly isolated ways of living. And in one of our chapters in our book Flourish, we look at how that situation might be flipped. So in evolutionary biology, for example, organisms combined to evolve into new, more complex ones. And that raises the interesting question of how we might start to shape our cities so that we actually foster that mutualistic behaviour, and it starts to become a kind of self reinforcing positive cycle that is the opposite of sprawl.

James Ogude 22:22

African cities have always been described as unplanned. And yet, when you look at it critically and closely, perhaps there's something that you can learn from African cities, obviously, African cities also mimic, you know, cities from the north in a number of ways: you will find your skyscrapers, you find your high rise buildings, and the face of the city is really concrete. And in certain ways, this more or less erodes the ethos of interdependence. And yet, studies in African cities point to something which is very interesting. That is, there's a sense in which people carry with them their communal networks that sometimes collapse the boundaries of class, boundaries of ethnicity, boundaries of gender sometimes, but perhaps more importantly, collapsing the boundary between the rural, and the urban, you know, the urban and its periphery.

Presently, I was reading a fascinating work that has been done on Jerusalem, and it focuses on what we would call environmental history, or built environment. And the argument that this scholar from Britain makes is that there's a sense in which the way that Jerusalem evolved was through the mimicry that was going on between the urban space and the rural spaces, and you will find that people are moving closer and closer to nature. So people would move to the periphery of the urban space, use local materials to build their houses, in ways that are not harmful to the environment, but also begin to grow their vegetables, what came to, to emerge was what we call urban agriculture, they plant their trees on a regular basis, and use those very trees, to build their houses, and sources of wealth.

So there's a way in which I believe that, you know, a sustained urban environment will have to shift fundamentally, the ways in which we look at our built in environment. I was looking at, incidentally, a documentary that was actually based on on Singapore, and I was fascinated by ways in which one of the architectures is trying to shift our thinking around, you know, the interface between nature and the building, so that you don't just build isolated buildings, but you have an integrated building where you can have grow your veggies, you can have your trees, you know, and these are things that we need to start thinking about, clearly, seriously, if we are going to save the Earth because, the impact of carbon emission can only be mitigated if we have a balanced understanding of how the environment has to be managed. And so that the dichotomy between urban and nature has to be challenged.

Sarah Ichioka 26:03

Thank you. I'm so happy you brought up Singapore, the city has been since independence has been so focused on greening its physical spaces. And now there's a real shift, since last year to a new vision of not no longer being a city in the garden, which gives a sense, it's still quite anthropocentric, right? It's the gardener is a cultivator through to the city in nature, which potentially at least that framing situates humans on a more equal plane with the other parts of natural systems that they're interacting with. I wondered if, if we could explore that a little bit further, in terms of the idea that you brought up earlier of how do we foster connections with the non-human beings in our community? Are there any stories or practices that you feel are helpful ways of thinking about how we foster those sorts of connections between humans and, and more than human?

James Ogude 27:06

Look, as I was reflecting I was taken back to my growing up as a young child in, in Africa, and, you know, in the evenings, we always listened to stories. I remember one of our stepmothers that always told us fascinating stories. These stories actually collapse the boundaries between the human and the non-human. There was such intimacy between human beings, and nature, and animals, and mountains. If there's any place, perhaps, in Asia, there's a bit of that, where the intimacy between the humans and natural landscape is so strong, you know, there's a way in which we can learn from some of these things. I come from a lake region, and the lake loomed large in our lives because it was a source of food. So people revered it. It was also the guardian of justice. In many ways, the assumption was that, you know, the lake gave, and if you became selfish about it, the lake will also take away from you, you know, in other many myths that have been in circulation of people who became arrogant, who became selfish, and lost all their wealth precisely because of that. And the lake, in a mythological sense, played a very important role, you know, as an agent of justice. There are ways in which we ought to push people back to see, you know, the world as a shared space of intimacy with the rest, sometimes living in tension, at times in harmony. But, as I was saying, it was a collaborative project, so that we live responsibly, you know, as we seek to care about our, about our world.

Michael Pawlyn 29:19

If we project forward, what would you say to someone, perhaps an architect, or an urban planner, who's convinced by the validity of this shift in thinking and wants to know how to accelerate this shift? How might we actively foster this kind of thinking and behaviour?

James Ogude 29:36

The one interesting thing, which I've realised is that, you know, architecture fundamentally, is also a very humanistic endeavour. The Ghanians have this story in which the daughter looks at the father, you know, staring into the past so intensely, and she says “Father, you're always looking at the past, into the past what's going on?” And the father says, “My daughter, because the answers to our current problems lie in the past.” And that may not be entirely true, but it carries a lot of truth, that there are certain practices that architecture can draw on, humanities have always lived with, especially mimicking their environment in ways that ensures that sustainability is at the core of every architectural work that you engage in. And I'm encouraged because there are more and more imaginative forms of architecture, that are grounded on green ecology, that are grounded on environmental sustenance. And I think, you know, the future decides precisely in focusing on those, those spaces that foreground, environmental sustainability going forward.

Michael Pawlyn 31:11

One of the biggest criticisms of modernism, particularly in the field of architecture was the way that it kind of swept away everything that had occurred kind of before 1920. It's taken us quite a while to realise that the folly of that and actually how it's remarkably similar to the obscenity of colonialism in the way that it swept away so much valuable knowledge. And it's been really encouraging to see some of that coming back to the fore with writers like Tyson Yunkaporta and Robin Wall Kimmerer, talking about Indigenous knowledge, and, and also certain books. And there's one by an architect called Julia Watson looking at the amazing ingenuity that exists in Indigenous cultures and the way that they managed to shape dwellings for themselves just using materials on the site itself. And so in many ways, it's a really exciting period that we're entering, you know, for all the terrifying challenges that we're facing. I think there's, there's so much we can draw on now for a much richer and more appropriate architecture.

James Ogude 32:15

I was– I visited Arizona a few years ago. We were having an Environmental Humanities meeting there, and we were put up in facilities that mimicked the Indigenous communities, the way they built, you know, their homes, it was amazing. The way it is structured it's cool enough, you don't need aircon in order to cool them down precisely because of the awareness of the environment within which they are living. Here in Africa, we used thatched houses very creatively, you know, and it's amazing that our tourist, you know, conservation areas have now gone back to the use of thatched chalets, where people stay. That is precisely because of their ability to conserve–it’s cold during the day and warm during the night. I still think there's space for us to be imaginative, to be creative, to adopt, you know, some of these knowledges and bring them to the present in ways that can mitigate against the kind of problems that we are talking about here.

Sarah Ichioka 33:41

We both heartily concur with that approach. One of the reasons why Michael and I wrote Flourish is that we know that we both like to read more than perhaps some of the other professionals working in the built environment that we know. Given that your expertise is as a scholar of literature and ecocriticism, what are the key pieces of literature that you think that architects and built environment practitioners could read and learn from to help give them a more holistic understanding of what action could mean, in the context of our compound global crises, including the climate emergency?

James Ogude 34:28

I'll give you one. Recently, I was reviewing a work of a young man from the University of Yale called Cajetan Iheka. You know, he has a fascinating title called Naturalizing Africa, which is a brilliant book, which really takes us back to, you know, the moment of rupture that led to where we are on the continent, reasons why the kind of problems that we are facing demise and it tries to trace these, obviously, to the advent of the empire and I found it to be, you know, a fascinating book, but it's also fascinating in the sense that it speaks to with a lot of clarity, against the past discourses that tended to centre the Anthropocene and argues, you know, for a fundamental shift towards human - non human, you know, relationship. So, Cajetan’s book, Naturalizing Africa is one recent book I have read. There is also work on post colonial, you know, ecologies.

Michael Pawlyn 35:41

I wonder if I could just return to the, one of the earlier questions just briefly, and it was when we were talking about, what, what does an embodiment of Ubuntu look like in an urban context? And you talked about urban agriculture as one brilliant example. Just wondering if there are any other examples that might help make this concept more tangible in terms of what might it look like… in terms of, you know, sort of social infrastructure that would emerge or forms of cooperative behaviour or shared amenities?

James Ogude 36:15

I think I mentioned this briefly, you know, one of the fascinating studies that have been done on African urbanities by Johannes Fabien. You know, he's an anthropologist, and one of the things that Johannes Fabien emphasises is the fact that in a number of African urban spaces, cooperative networks, you know, which brought together communities around a range of issues, whether it was caring for one another, when they were sick, or when when people die, what do you do? How do you offer support? In South Africa, it even moved into the space of microlending, where you found that when mainstream financial Euro banks could not give people loans, they always came together. You know, there's something called stokvels here in South Africa, which is thriving, and it's a cooperative, you know, entity that brings people together, you find a group of women coming together, they pool their resources together, and they use those very resources, you know, to fulfil forms of, of business among their members. Either they start their own business or lend others, those are fundamentally Ubuntu-ish. And those networks, I can assure you, all over the continent that I've learned that similarly in certain parts of Asia, they are common practices.

Sarah Ichioka 37:58

I also appreciated how you've spoken about it as a reference point for governance as well or in a reconciliation context, as well, which I think is something that we all need to be thinking about how we can apply philosophies of this sort, both from the scale of, you know, how our everyday community might be constituted through to things like conflict resolution, right, between groups at a national level, I found that part of your work very insightful.

James Ogude 38:30

The idea of social imaginaries has always been fundamental to some of these ideas. You know, if you look at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, that's a fascinating dialogue that was created between Ubuntu and Christian value systems, what the Archbishop Desmond Tutu called the Dei Imago theology, you know, in which he says, we're all made in the image of God, so we ought to be the same. Ubuntu places emphasis on sisterhood, brotherhood, and conviviality, between people, is there a way in which we can see each other, you know, through the prism of Ubuntu, without feeling that it belongs to some people? It is ethnic, so has nothing to do with us. And I think that is why Ubuntu has taken off. People have taken to it with so much passion. I get on a daily basis, people are doing their PhD theses, their master's work, inspired by the concept of Ubuntu.

Sarah Ichioka 39:39

As more people around the world start to discover and get excited about Ubuntu, do you think there could be any risks of cultural appropriation? Or do you have any concerns that the concept could be diluted or misunderstood?

James Ogude 39:54

Well, it's not just outside, even here, the concept was hijacked by politicians, who basically, you know, throw it around to do whatever, whatever they want. And one of the reasons the Templeton World Charity Foundation at had just given the Archbishop Tutu an award for his spiritual work, and attempt to bring people together that can study this concept to deepen it, you know, understanding of it beyond the political rhetoric, and there's always a danger with all philosophies and concepts, when we use them out of context. And when they travel to other spaces, we must insist that they're inflected in those spaces. And obviously, there will be appropriation, misappropriation of some of these this concepts, but the idea is that when I'm a very strong believer in Edward Said’s idea of travelling theory, you know, that when theories travel, you know, you don't just take them for what they are, they have to be domesticated in new–in new spaces, in order for them to be relevant to various people and I would imagine that as Ubuntu travels, that's why my work is moving towards a comparative approach. What is it that we can find in other societies that resonate with the values of Ubuntu? And how can Ubuntu therefore, enter into dialogue with some of those value systems in new lands.

Sarah Ichioka 41:42

I think that resonates with Michael's and my approach in our book where we're trying to describe different facets of regenerative design practices. But we understand that the term regenerative originates in agricultural circles. So you have to examine very carefully what did it mean in that original context now, as you try to translate it across more broadly to other cultural or professional practices.

Michael Pawlyn 42:07

How can our listeners learn more about your work?

James Ogude 42:11

I'm currently working on an ongoing book project that is dealing with banished knowledges like Ubuntu, and basically asking how they can contribute to the protection of our environment and also asking what the world can learn from them. You know, especially because some of this knowledge is had been pushed to the margins, you know, when it comes to modes of knowing or modes of being in the world. So that is the one thing that I'm busy with. The second thing is going to be a while, right…

Michael Pawlyn 42:51

When will that be ready?

Sarah Ichioka 42:53

When is a book ever ready, Michael? (Laughter)

James Ogude 42:58

I don't want to pretend. (laughter) We are looking, we are looking at, you know, at the very earliest 2023, early 2024. You know, it's a long way. But we are, we have a book that is coming out with Routledge on environmental struggles in Africa and resource exploitation, which is really one of my areas of interest that is going to come out, you know, next year.

Michael Pawlyn 43:32

And there are the existing books of course, like the one titled Ubuntu and the Reconstitution of Community.

James Ogude 43:38

Yes, I love that book because of the idea, what it speaks to, in relation to the constitution of the community. Ubuntu and the Everyday and Ubuntu and Personhood. But I'm trying to push the debates in those books, to move them forward. You know, because as a scholar, also, you suddenly discover that there were so many gaps, when I realised that there's a way in which, you know, these concepts can speak to environmental environmental issues. So, finally, the one thing that we are we are looking at is environmental struggles and resource extraction in Africa, and climate justice, and problems of scale. Here we are working with a number of universities, from North America, Australia.

Sarah Ichioka 44:30

I just wanted to thank James, to thank Professor Ogude, for his amazing sharing, we will be watching with excitement to see what new scholarship comes out of your and your colleagues’ work at the African Observatory for Environmental Humanities. So thank you so much for making time in your very busy schedule.

Michael Pawlyn 44:54

Thank you very much indeed.

James Ogude 44:56

Yeah, thank you, too.

Sarah Ichioka 45:00

Okay, so after that conversation with Professor Ogude, I have to take six months off to just spend in the library reading all of the amazing references.

Michael Pawlyn 45:10

So many references. (Laughter)

Sarah Ichioka 45:11

So intriguing and inspiring. I think what I took from it was the essential importance of exchange between disciplines. And between cultures. And, you know, the way he was talking about what the humanities can offer, to debates that have so often been dominated by the natural sciences. And indeed, just the examples he gave of resonances between African philosophies and other philosophies from Europe, from South Asia, etc. How about you, Michael?

Michael Pawlyn 45:54

Yeah, I really liked the way he talked about how ideas travel. And you need to think about how you apply them in different contexts. So I thought he gave a really interesting answer to your question about the potential dangers of cultural appropriation. And one of the things that occurred to me while reading his books in preparation for the interview was just how much more inspiring the African philosophers he refers to are you know, compared to the European philosophers. And so the material about Ubuntu was so so much more energising? At least that was that was my reaction to it.

Sarah Ichioka 46:34

It just underscores the reason why so many young people are advocating now for, you know, future ready, curricula that include many more perspectives from many, many different cultural traditions, as well as you know, including the skills and mindsets that we're going to need to face the future that we've inherited or build the future that we want.

Michael Pawlyn 47:00

It actually reminds me of that student campaign for pluralism in economics. It was a pretty substantial kind of intellectual revolt against the way it was taught calling for a much more plural set of perspectives from different parts of the world, from feminism and from ecology, and so on. And I feel in a way we need to do very similar things with our built environment education systems, so that they do have a more comprehensive globalised view.

Sarah Ichioka 47:40

If you're interested to learn more about principles of regenerative design, or any of the many fascinating topics that we've been discussing together today, you're warmly invited to visit our website, which is simply: www.flourish-book.com. That website will also include links to all of our socials. The podcast is sponsored by Interface, and based on the book, Flourish: Design Paradigms For Our Planetary Emergency by Sarah Ichioka and Michael Pawlyn.

Michael Pawlyn 48:17

Our sponsor interface has a takeback programme called reentry, that takes old carpet then seeks to reuse and recycle its products at the end of life. On the reuse side. This has seen its face cooperating with reuse businesses and social enterprises in several markets. Looking to build this emerging market for secondhand interior products in a world that so used to the cheap and the new, its products are then used for the fit out of offices for SMEs by community groups and even appear in social housing, giving their products a more impactful life but one that isn't tied to a single use. So collaboration, co-innovation, and the mutual need for manufacturers to play an important role in creating secondary markets will be key to a circular economy. Moving from a nice-to-have to the norm.

Sarah Ichioka 49:11

The Flourish podcast is recorded at Cast Iron Studios in London and the Hive Lavender studios in Singapore. Our co producers are Kelly Hill in London and Shireen Marican in Singapore. Our research and production assistant is Yi Shien Sim. The podcast is edited and features brilliant original music by Tobias Withers.

Flourish Systems Change is brought to you by Interface

Production credits

Presenters Sarah Ichioka & Michael Pawlyn

Audio producer & composer Tobias Withers

Producers Kelly Hill (London) Shireen Marican (Singapore)

Research and production assistant Yi Shien Sim

Podcast cover art by Studio Folder

Special thanks to Ayanda Sihlahla